Henry Friedman

Born: Nyíregyháza, Hungary, 1931

Wartime experience: Ghetto and camps

Writing Partner: Chris Dingman

Henry Friedman was born in Nyíregyháza, Hungary, in 1931. In April 1944, one month after the German occupation of Hungary, Henry was forced into a ghetto and then to a collection point, from where he was deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau.

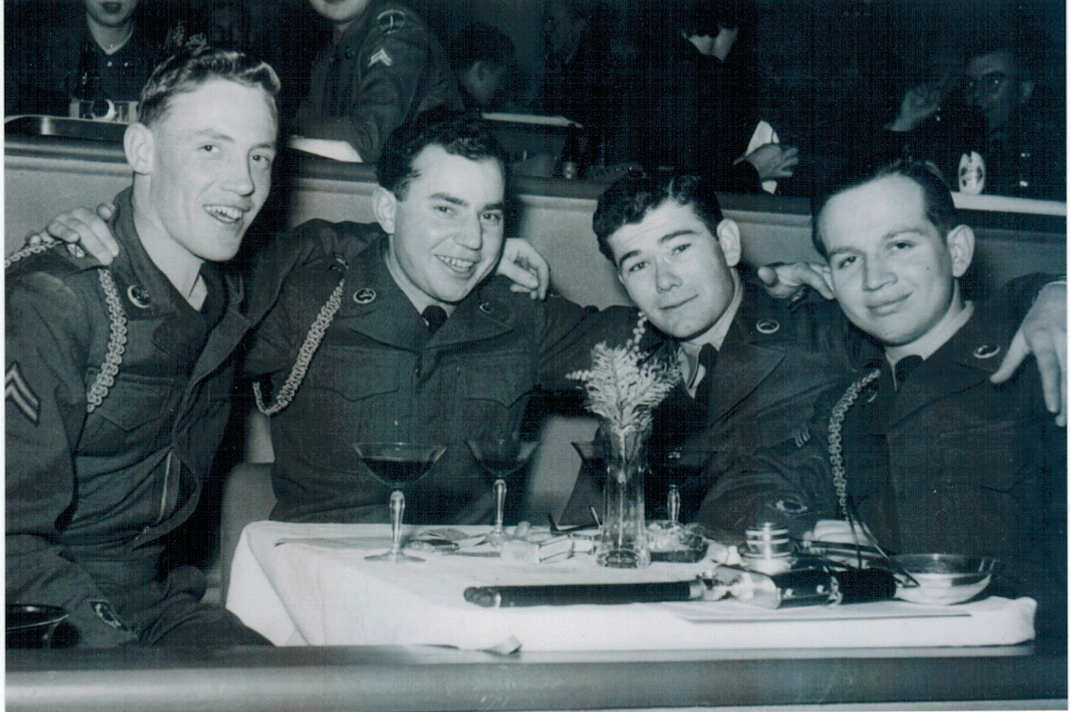

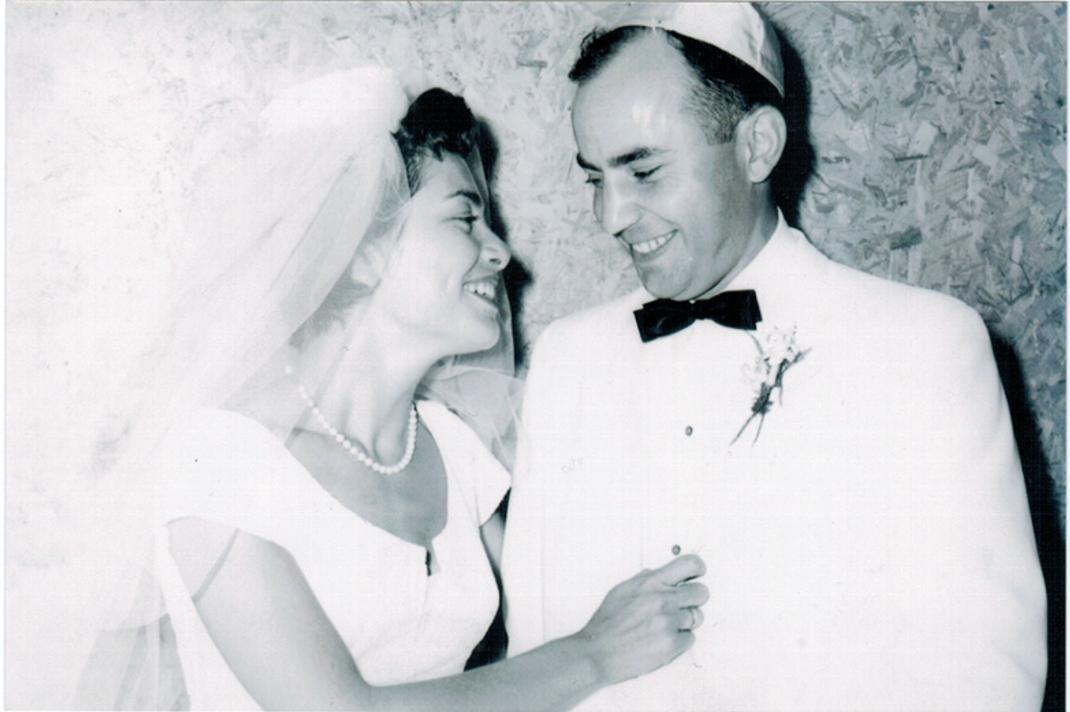

He was sent to work at the Monowitz-Buna subcamp, and in January 1945, to the Gleiwitz subcamp and then on to the Mittelbau-Dora concentration camp. In March 1945, he was sent to the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp and was liberated by British forces one month later. After the war, Henry left for Sweden, where he started to recover and continue his education. In 1947, he immigrated to the United States, finished high school and was drafted into the US Army. Henry moved to Canada in 1958 and married his wife, Reny, in 1959. In Toronto, Henry raised a family, reunited with his surviving brother, and worked in real estate. Henry passed away in 2019.

The Occupation of Hungary

No one actually expected the Germans to occupy Hungary so we were not worried when, as we finished our Friday night meal around 9:00 p.m. on March 17, 1944, we heard the air-raid siren go off. My brothers, Erno and Emil, and I went outside to see what was going on. We thought that we would see some British or American airplanes but we didn’t see anything. We talked about what would happen if our town was bombed but we thought that there was nothing strategic to bomb in Nyíregyháza. While the sirens were going, we noticed some army movements but no one knew what was going on. The Germans, with their war effort on the Eastern Front shrinking, decided to occupy Hungary on March 19, 1944. The Germans had double-crossed the Hungarian government and started to move troops into Hungary. The first couple of days were quiet and everyone was concerned, but nothing of note happened. Then we started to see German military vehicles and soldiers by the thousands going through the main street of our town and some of them stayed on as occupiers.

While the occupation was underway, the whole Jewish “question” came under SS military rule and the world caved in for Hungary’s Jews. The first set of rules came out just weeks later. All Jews had to wear a yellow star so that they could be identified from a distance. Then came the curfew, ownership restrictions and other anti-Jewish laws. It was enough to put everyone into a state of shock. After a month, during the holiday of Passover, the authorities decided that all Jews had to move into a ghetto. My brother Erno decided that he would not go with us and would instead use false identity papers. My father and mother were happy about this — at least Pubi (Erno’s nickname) would escape from this mess. The next day, he was gone. Unfortunately, to this day, no one knows what happened to him during 1944; he disappeared without a trace.

Everyone was given forty-eight hours to get ready to move into the ghetto, to prepare food and pack whatever they could carry. My mother started to make dry cookies; they were made with oil and would not spoil for six to twelve months. The cookies were for emergencies only and I was in charge of carrying and protecting them. Forty-eight hours passed and a wagon showed up at our yard. The wagon was loaded quickly and, within minutes, we were moved to the synagogue on Síp utca and from there we were sent to a house in the ghetto. When we got to the house, we found about twenty families already there. We were allocated a ten-by-twenty-foot area in a room with others. The sanitary conditions were very bad, so the first thing the men had to do was dig trenches for outhouses for men and women. It was our new place to live and it was beyond our imagination and so humiliating. We couldn’t even leave the ghetto without a permit.

All this took place within an eight-week period and in such a way that no one could be in touch with one another to learn what was happening. No one was allowed to visit anywhere, there were no phones in the houses and if there was a phone, it was disconnected or, worse, listened in on. Everything had happened very quickly. We assumed that all our relatives were having the same experiences as we were. It was a chaotic nightmare.

Unanswerable Questions

In the morning, the men that were chosen as not qualified to work were separated from the rest. I was very concerned about my father and how he made out. I figured that after supper I would make a dash to his barracks to see him. All day I had a bad feeling. Finally, I got back from work. I ate only half of my supper and ran over with the leftovers to my father’s barracks. As I approached his bed, I saw that the straw mattress was rolled up and he was not there. I sat down at his bedside and started to cry uncontrollably. I asked the men next to his bed if they knew where my father was and they just shrugged their shoulders and shook their heads — they did not know what to say. They didn’t have to say anything — their faces told the story. I stayed by the bed for about five minutes. I figured there was nothing that I could do. As I was leaving, I thought to look in the mattress; maybe I would find something there? As I pushed my hand in I felt something. It was the white angora scarf and rolled up with it was the steel spoon I had given my father. I had ground down the handle of the spoon so it was also like a knife. I understood, then, that my father knew where he was going and that he would not need his scarf or spoon. I let out a scream so loud that everyone in the barracks turned around to see what had happened. I noticed that everyone was watching me so I decided to leave and go to my barracks.

I was still hoping that my father had been left behind. All the way to my bunk, I was thinking of how I could find out what happened to him. I figured that on Saturday I would go to the camp office; the head counters there might know. In the meantime, my tears did not stop until I fell asleep that night.

Saturday came and I got myself ready to go to the camp office to see if they could answer my questions. I went to see a young and sympathetic fellow inmate. He said that he had no record and that he didn’t know what happened to my father either. And so, my doubts hung on with my hopes that maybe someday I would see my father again.

My father, Adolf Abraham Friedman, was most likely killed the next day. He must have known he was heading back to Birkenau, to the gas chamber, with hundreds of others and that there was nothing he or anyone could do. I presume he knew that the end was near for him and that he made peace with his conscience and was ready to die. But how can one feel, knowing that he is being taken to be killed like an animal in a slaughterhouse? No one in the camp had a pencil or paper, so my father was not able to leave me a few chosen words. Fifty years later, I still wonder what he would have said to me in those chosen words: Would he have apologized for not getting us all out of Europe to America or the Land of Israel? Would he have said that he was sorry that he had sired children into such a crazy, mixed-up world? Would he have blamed God for all this misery we had to endure simply because of our religion? Or would he have left a few instructions for me on how to try to survive and endure the misery yet to come before liberation?

My father was a man who would not kill a worm or step on an ant on the ground — he would go around them because they were God’s creations. Would my father have been praying to God, who had forsaken him? Did he pray to God that his children might survive? Was he still hoping that something might change and he would somehow survive? Was he glad that he didn’t have to say goodbye face to face to his youngest son, whom he loved dearly? Was he cursing God for misguiding him and the whole Jewish people, for that matter the whole human race, permitting men to commit the most unimaginable crimes in all of history? Or was he just carrying the subconscious guilt and burden that Jews have carried with them for centuries — the guilt that so many Jewish people have taken for granted — that he was to pay the price at the cremation? I shall never know what he was thinking or doing but one thing is sure — I felt uncomfortable then and still do today. When I think about it, I feel uncomfortable. Probably, I shall carry this anguish with me until my last breath on this earth.

I pray that my father’s soul may rest in peace.

I stopped crying that night. I always wondered why that feeling dried up in my brain and body — was it to fight back God’s will as I understood it? Did I mature overnight to the point that crying was a child’s custom, a useless custom? I have wondered about this for seventy years and have not been able to come to any conclusion…

Thirteen

That October, I turned thirteen years old in the camp. I wanted to celebrate my bar mitzvah so I asked some older people and they said they knew a rabbi and that I should go to him. His name was Rabbi Jungreis and he was from the town of Szeged. The rabbi told me to come back to his barracks on Sunday afternoon at 1:00 p.m. He said he had a tefillin (phylacteries) that he had secretly brought into the camp and that he would show me how to put it on. I went to meet him that Sunday and he took the tefillin out from under his mattress. The rabbi told me to roll up my sleeve. I said the prayer, and I started rolling the tefillin on my arm. Suddenly, the door to the barracks opened. The rabbi told me to stop while he went to see who it was. The Stubendienst came in and the rabbi told me to take everything off. Instantly, everything went back under the mattress, hidden from sight. He told me to leave the barracks and, as he walked with me, he told me that he was afraid of problems because the Stubendienst was a bad person. He told me that I had done a good deed in God’s eyes and that the intention of doing something good is more important that the deed itself, so he made me feel very good. As I walked away, I promised myself that one day in the future I would have my bar mitzvah.

I finally did have it, on November 10, 2012, when I celebrated my bar mitzvah with my grandson Zachary Friedman as a bar mitzvah boy of remembrance. It was a day of grandiose celebration of unequalled proportion. To think that, at age eighty-one, I was still around and able to enjoy it to the fullest with my family! In Zachary’s address that day, he reflected on the many children who never had a chance to mark the occasion of coming of age: “The truth is, I can’t even imagine it [my grandfather in a concentration camp]… I am very proud of my Opa and to share this special day with him but I also remember the one and a half million Jewish children who were killed during the Holocaust, many never celebrating their bar/bat mitzvahs.”

The Death March

After marching all night on January 18, 1945, and the early morning on the 19th, we finally arrived at our destination — Gleiwitz. It was probably around 5:00 a.m. We had completed an eighty-kilometre journey that came to be called the death march. It was still dark so I did not know where we were. The group that I wound up with was let into a warehouse-type room with very dim light. Everyone was exhausted and there was not enough room to stand, never mind to sleep. Even so, we were glad to be inside, out of the wind and cold. I was not able to sit down on the floor, as there was no room. I stood with someone’s leg between my shoes so I crouched down slowly into a squatting position. Before I knew it, I was deep asleep with my blanket on top of me.

I do not remember how long I slept but I must have slept through the day and night. When I awoke, it was early afternoon and the sun was shining through the windowpane above the door where we had come in. The sun felt warm, but I could see my breath in its rays. I felt no pain and was very relaxed. It was very quiet except for someone hammering outside. I looked around and almost everyone was gone except for about fifteen people, who were still sleeping on the floor. I figured it was time to look around so I tried to get up but I could not move my legs and had serious trouble moving my body. I started to move my hands by stretching them and after a few tries they felt all right. Then I stretched my neck and shoulders, but my legs would not move. So I decided to tip my body to the floor and try to move my legs sideways. It felt like my legs were paralyzed from my thigh down. Slowly, after about fifteen minutes, my blood started to circulate and my legs could move. Luckily, I was able to get up, but my knees were not cooperating and were quite stiff.

I felt I should see to those people on the floor so I went over to one of them; he was half-naked, with no blanket or jacket. I pushed him a little and realized that he was dead. I went over to the next man and found the same thing; he was dead too. I figured I better get the heck out of there.

I started to wonder what had happened to me, how I had slept through the whole day. Why did the SS guards let me sleep? Perhaps they tried to wake me and thought that I was dead too. Even today, seventy years later, I have no answers. I may have been in a coma.

One thing that has stayed with me ever since that night is that I cannot cry. I cannot cry for anyone’s death or for any pain that I may feel; however, I did have tears in my eyes when my brother died many years later. In plain language, I stopped crying that night. I always wondered why that feeling dried up in my brain and body — was it to fight back God’s will as I understood it? Was it a psychological deficiency that happened during that sleep? Did I mature overnight to the point that crying was a child’s custom, a useless custom? I have wondered about this for seventy years and have not been able to come to any conclusion and will probably never be able to fathom the reason for something like that to happen. Thankfully, I am able to cry tears of joy — which I did at my wedding, my children’s births, my son’s wedding and my grandchildren’s births.

In time, I was able to get to the door but, before I opened the door, I thought to take an inventory; my blanket was on top of me, my angora scarf was on my neck, my spoon and tin dish were still with me — my whole fortune.

I started to walk slowly, trying not to be noisy with my wooden shoes. Besides the SS guards, there were no people around. As I walked, I passed a table with salami and a table that was half-full of twenty unsliced rolls. I thought to myself, how could I get one of them? The guard was busy setting things up so I walked up to the table, stopped and looked at the food. The SS guard was looking sideways and without fanfare I asked him, “Kann ich ein Stück haben? (Can I have a piece?)” He did not chase me away nor did he reach for his gun. I walked a little closer to the table so that the blanket that covered me was also on the table to the left of me and the SS guard was to the right of me. I put my hand on a whole double-sized salami or wurst and, in a split second, I tucked it under my blanket, walked back a few steps and then I put the salami under my jacket so that it would not fall out. I walked two more steps, stopped and turned around to thank him with my eyes and I saw him looking at me sideways as if to say, “Smart boy, enjoy it.” I must have looked awful; perhaps he felt sorry for me and he could not figure out where the heck I had come from or how I had made it this far. I turned away and I walked about ten metres farther where I noticed a similar table with bread. I felt I must have bread with the salami so I tried the same thing as before and quickly secured the bread. I could not believe it, but it worked too. It was a miracle that this should happen to me. I felt like I had hit the jackpot!

The SS guards could have reached for their weapons and there would have been one less to feed but they chose to act honourably toward me, a mere child. We can learn from this story: It is wise to hate ill-guided systems of government, but it is counterproductive to hate individual people for being part of dictatorial groups like fascists, communists or some religious groups or races. For anyone who hates individual people, without mercy, becomes himself an unhappy human being.