Freda (Franka) Kon was born in Lodz, Poland, in 1922. In February 1940, five months after the German occupation of Poland, Freda and her family were living in the area that became the Lodz ghetto.

Freda worked in a kitchen in the ghetto and met her future husband, Lolek (Leo), there. When the ghetto was liquidated in August 1944, Freda and her family were deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau. A few weeks after their arrival, Freda, her mother and her sister were sent to the Stutthof concentration camp, and three months later they were sent on to a subcamp of Stutthof called Schippenbeil (now Sępopol), where she was forced to work at a military airfield. The camp was evacuated in late January 1945, and Freda and her family were forced on a death march, ending near Palmnicken (now Yantarny, Russia), where most of the prisoners were massacred. Freda, her sister and her mother were lucky to escape that fate and were liberated by the Soviet army in early February 1945. They eventually returned to Lodz, and Freda later reunited with Lolek. They married in October 1945 and lived in Lodz, where their daughter was born, until 1949, when they left to join family in Israel. In the early 1950s, Freda and Lolek left Israel for France and then Canada, settling in Toronto. Freda worked in beauty salons, volunteered at Baycrest’s Jewish Home for the Aged and was very involved in the Yellow Rose Project, a prom for Holocaust survivors. Freda lives in Toronto.

Meeting Lolek

The Germans had organized the ghetto, but they had also appointed Jewish leaders within the ghetto as go-betweens to take care of the day-to-day running of the ghetto. Chaim Rumkowski was appointed by the Germans as head of the Judenrat, the Jewish Council, known in the Lodz ghetto as the Council of Elders. The Germans gave orders and expected the Judenrat to provide what the Germans requested. Rumkowski, with other members of the Judenrat, organized for the needs of the ghetto, which included providing schools, soup kitchens, religious organizations and synagogues, cultural programs, employment opportunities through factories, stores, restaurants, hospitals and charities, places for burial, as well as a Jewish police force. Food had to be brought into the ghetto from outside. Rumkowski believed that the Jews in the ghetto should provide what the Germans requested in order to keep the people employed and to garner favour with the Germans. In this way, he thought he could save the Jews of Lodz.

I was young and wanted to have some fun in my life. I wanted to see people and talk to people, as did many others. But because of the curfew, we were not allowed to go out to the street to visit friends or family. Everyone had to be in their homes by 5:00 p.m. unless they had a special permit. There were partitions between the backs of several apartment buildings, so we took down the partitions and got together in the area that was like a courtyard behind the apartments. We could also go visiting and sneaking from one apartment to another through this back way.

I was fortunate to get a job in the kitchen of what was called the intelligenzküche in German, the canteen for the intelligentsia, the more privileged Jews in the ghetto. I could get a bowl of soup at work, which meant that when I came home, I didn’t have to eat supper, and the others in my family could have my ration. The manager of the kitchen was Helena Rumkowska, sister-in-law to Chaim Rumkowski and wife of his brother, Jozef. I met many very nice girls there who had been in high school. Even though I hadn’t gone to high school, I had the privilege of working there. The canteen opened at one o’clock. One day a family came — a mother who was a doctor, a father, two daughters and a son. Some of the other girls were talking about the son, saying, “Look who’s there — Lolek Kon.” I took a peek to see who they were talking about. I didn’t know him or any of his family then, but I soon made his acquaintance. When he came to the restaurant on his own, I felt his eyes on me, and then he came to my table and didn’t leave until closing time. I was seventeen years old when we met.

Lolek had been studying textile engineering in Belgium. He had returned home on vacation, and with the German occupation of Poland he was unable to return. Lodz was known as the textile centre of Poland, and many parents sent their sons away to get textile engineering certifications.

From the beginning of 1942 and throughout the year, the Germans came into the ghetto to arrange the deportation of residents. They ordered us out to the backyard of our apartments and told us to get in line. They took out older people or younger people, putting them onto trucks and wagons. We never heard from them and we never saw them again. We didn’t know where they went. Then we had to return to work. We later found out that they had been sent to the Chelmno death camp, where they were gassed on arrival.

At the time we didn’t know about Auschwitz, Chelmno or Treblinka. If someone mentioned “camps,” we didn’t understand what they meant. In the ghetto there was cold, hunger, starvation and disease. My father was making shoes from shmattas, rags. Whenever we found a discarded blanket or cloth, my father would make shoes. Whatever was going on around us, our family, at least, still came home every night.

In September 1942, Rumkowski ordered the residents to come to a particular location with their children. The Germans had ordered the deportation of all the children below ten years of age, as well as the elderly and unemployed. As Rumkowski made his announcement, there were screams and cries, as well as denouncements of the Judenrat. Rumkowski claimed that if he didn’t give the Germans the children they would come into the ghetto and butcher everyone. Many parents were unwilling to let their children go alone. When the children were taken away, everyone was crying; the gevalt and the geshrayen (shock and cries) were heart-wrenching.

From the beginning, Germans frequently shot people. And as I mentioned before, there were public hangings. The hangings now increased, and we had to go to witness them.

The ghetto was surrounded by fences and barbed wire, with armed soldiers guarding all along the perimeter. There was still a curfew in place, and we now had to be home by four o’clock in the afternoon. One day I had been someplace and was out past four. Two German guards were standing nearby. One of them asked me in German, “Why are you out?” I replied, “I was working.” One of the soldiers wanted to shoot me. The other one told him to let me go. He didn’t let him harm me. As I started to walk away, I feared that the first one would shoot me in the back.

Lolek wanted to marry me. I told him to go speak to my father. My father said to him, “You would like to marry my daughter. It isn’t good to marry during a war. For us this is the second war. Who knows what will happen or what will be. But I give you my word — my word is more than money. If you both live through the war, Franka will be your wife.” I was anxious to hear what my daddy had told Lolek. When he returned he told me we would marry after the war. He promised! His word remained!

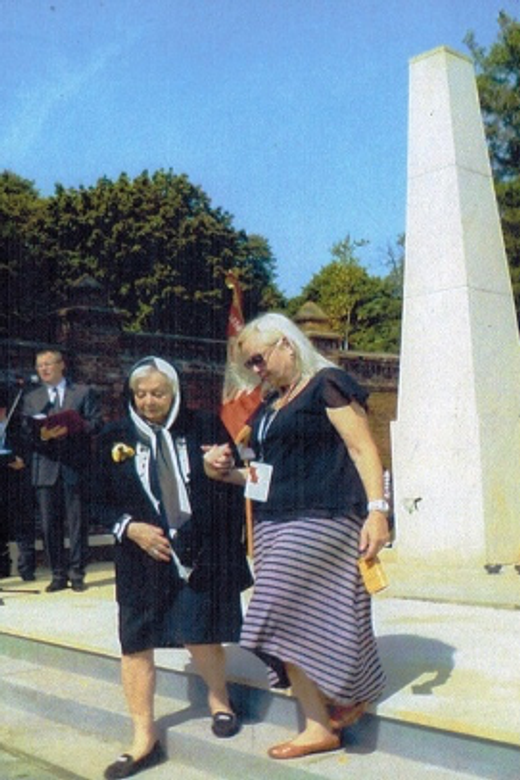

Freda (front, second from the left) standing near Chaim Rumkowski, head of the Jewish Council, at an event in the Lodz ghetto. Poland, circa 1941. Courtesy of Yad Vashem.

Freda (standing third from the left) at an event at her workplace in the intelligenzküche, the canteen for the intelligentsia, in the Lodz ghetto. Poland, circa 1941. Courtesy of Yad Vashem.

The Last Camp

After three months in the Stutthof concentration camp, the Nazis loaded us into open cars on a train. We didn’t know where we were going, and we all took a good look around to see what there was to see. I saw a dog, a cat, trees. I felt that I was seeing things that I hadn’t seen for years. I even saw children playing. We were wondering why and where we were being taken.

We were taken to another camp, Schippenbeil, now known as Sępopol; then it was in Germany, but now it’s in Poland. There were no gas chambers at this new camp. But beside each set of barracks there were ammunition reserves. We were afraid that the ammunition could blow up. Sometimes it did.

I still had the needle that my sister’s friend had found for me. I went to the SS woman in charge and told her that I could sew. I told her I could sew drapes or clothes. She brought me some clothes from people who had been killed. I pulled out the threads and made all kind of things. I told her that I had my mother with me. Apparently, if the guards found out that mothers and daughters were together, they would separate them, but this SS woman seemed to have a heart. I asked her if she could find a job for my mother in the kitchen. They could always use extra help in the kitchen. She put my mother in the kitchen, peeling vegetables. My mother didn’t have to go out into the cold.

We were there for several months building an airport, moving wagons with stones back and forth. During the winter, we found empty cans and scooped up the snow. We warmed it up a little. Snow became the water for the day as food became scarcer. It was all we had to drink during the day until returning to the bunks at night. That snow saved us.

At six o’clock in the morning, we had to go to roll call to be counted, to make sure nobody was missing. One morning I found a piece of paper, which I carefully picked up so no one would see me. I put it on my mother’s back to give her a little warmth and protection from the snow and bitter cold.

Everyone suffered from lice, which were eating people alive as well as infecting many with diseases. One of my fiancé’s sisters suffered from typhus. She became delirious and was sent to the infirmary. One day, a truck arrived to take away all those in the infirmary. I can still see it as if it were happening now. The other sister, who wasn’t sick, rushed to go on the truck with the sister from the infirmary. I said to her, “Anishka, don’t go. You know what they are doing with the sick people. They are going to shoot them or burn them. Stay with us. We don’t know where we are going to be. But we’ll be together.”

She took her hands, put them on her hips and looked right at me and said, “Franka! Would you leave your sister or mother if she were so sick? And even if you lived through the war, could you live with yourself for letting your sick sister go by herself?”

What could I say? Those were her last words to me, I swear. I never saw her again.

Now there were three of us — my mother, my sister and me.

I was now twenty-two years old. When I was seventeen, I had been incarcerated in the ghetto with my family. Five years of war had passed, going from death camps to labour camps to death marches. I was losing hope.

Starting Life Again

The eighth of May 1945, Victory in Europe Day, went by, and we were walking in the wilderness. We saw how the sky was illuminated — whether from ammunition or fireworks, we didn’t know — and asked the next person we saw what it meant. We were told that it was the end of the war. But what did that mean? Here we were, not knowing what was going on, where we were or what was going to happen with us. We felt such bitterness. We couldn’t grasp it — we couldn’t take in what it meant, the end of the war.

We eventually arrived in Lodz, but we didn’t have anywhere to go. So we went to our old apartment at Rybna 11. I knocked on the door, and a woman answered. After I explained who we were, she shut the door and yelled at us to get out of there. We were just trying to find a place to sleep at night. We slept on the ground outside the apartment.

The following day, we asked someone if there was a Jewish committee. We wanted to let them know that we had come back from the camps. We were given the address and we went there. The Jewish Committee office was set up in an apartment building. Survivors who arrived in Lodz registered there, and anyone searching for survivors came there to find out where someone was staying. When I walked in, one of Lolek’s friends recognized me and called out, “Franka, you are alive! Where is Lolek?” I told him that I didn’t know and that we had just arrived. I asked where we could sleep, since we had nowhere to stay.

We gave our names to the committee — my mother, my sister and me. No one else from our family had registered. We didn’t have a penny or a home. Different people started to take us in. We were sleeping in a different place each night. Eventually a friend of my sisters let us stay with him in his apartment. That became our address. We washed and tried to restart our lives. I started to work. Lolek’s friend asked if I could work with them.

The Red Cross gave me a little job to earn some money. I was registering newcomers to Lodz and taking them to a place to stay, like an emergency shelter. They set something up in a factory without windows or toilets. When anyone came to register, I asked if they had heard anything about my father, my brother or Lolek. No one had any information.

I was now twenty-two years old. When I was seventeen, I had been incarcerated in the ghetto with my family. Five years of war had passed, going from death camps to labour camps to death marches. I was losing hope.

Each day my mother waited at the door for me to return from work. Her first question was always, “Franka, did you hear something from our people?”

On this day, I turned to her and said, “You know, Ma, I think we have to stop thinking about the others — nobody has heard anything, nobody knows anything…”

As I was saying these words to my mother, somebody started knocking very loudly on our door — like the police would knock. I ran to the door and asked, “Why are you knocking like this?”

And standing there at the door was Lolek! He had arrived at the committee room ten minutes after I had left for the day. They told him that I had just left and let him know where he could find me. He came. My mother always told me, and this I will never forget, that when we saw each other we didn’t cry. We moaned. She thought we sounded like hyenas, moaning to each other, in a state of disbelief.

He stayed with us. We were so thrilled that we were each alive. His goal was to be in Lodz for May 24; he wanted to be with me for my birthday.

Then he told us the news about the family. He told us that his father was alive and that my brother and my brother-in-law were alive. My father did not come back. He had perished.

Lolek had come back to Lodz, but the others were left behind in the camps. They didn’t know that we were alive. The problem was how to get that information to them. Wherever people went, they searched for relatives and friends. Everyone was looking for someone. It was an extremely emotional time.

The day after Lolek returned, he was ready to go out. The clothes he wore didn’t fit properly. He wore a jacket that was too short for him. His hoyzn, pants, came down to his knees, like lederhosen. We managed to get him some other clothes so he wasn’t going out with short pants. We wanted him to look respectable. When he was at school in Lodz, there had been Jews and non-Jews in his class. As soon as he went outside, he ran into one of his old non-Jewish classmates, who exclaimed, “Oh, Lolek, you are alive, you are alive!” His friend gave him fifty dollars, so right away he was able to buy us food. That’s how our lives started.