Bracha Scheinman

Born: Antwerp, Belgium, 1930

Wartime experience: Camps and hiding

Writing Partner: Jehan-Jean Baptiste

Bracha (Berthe) Scheinman (née Silber) was born in Antwerp, Belgium, in 1930. When Nazi Germany occupied Belgium, she and her family escaped to France.

There, they were captured by French police and sent to a detention camp near Toulouse. They escaped the camp and found their way to a Red Cross refugee camp and then to the village of Éauze. In 1942, Bracha’s parents sent her to a children’s home in Faverges near the Swiss border, run by the Croix-Rouge suisse - Secours aux enfants (Swiss Red Cross - Children’s Aid). While she was in the home, Bracha’s parents and sister Sara were taken to the internment and transit camp of Drancy and then deported to Auschwitz. Bracha stayed in the children’s home for thirteen months and was then smuggled into Switzerland and sent to a Jewish orphanage in Basel. After becoming ill, she was sent to a sanitorium in Davos, where she was when the war ended. In 1945, Bracha, the only member of her immediate family to survive the Holocaust, left Europe for British Mandate Palestine, where some of her surviving relatives were living. There, she lived on a kibbutz and studied in an agricultural school. She met her husband, Jack Scheinman, and they started a family together. They moved from Israel to Toronto in the late 1950s. Bracha Scheinman passed away in 2020.

Changing Atmosphere in Antwerp

Our family home was a happy, idyllic abode for me and my sister. My parents were gregarious and would often host friends from Poland or from my father’s work or the synagogue. My father was a gifted tenor, so much so that people would frequent our house, especially on religious holidays, just to hear him sing. I relished being in this milieu. On Passover, I used to beg my parents to let me stay up till the entire seder was over — which was usually three or four in the morning. No such luck was afforded me. Some things about the way we lived boggled my mind: like on the eve of Shabbat, non-Jewish or “Shabbat gentiles” (shabbes goyim) were hired to do certain tasks that were forbidden to us, such as turning on a light switch, stove or furnace. Why couldn’t the grown-ups do these things themselves?

I remember my mother as a devoted wife, homemaker and caregiver who knitted and crocheted her daughters’ clothes. She would also make tantalizing desserts for us to devour. Friday nights, my mother lit candles. Father went to synagogue on Fridays, Saturdays and holidays. Sometimes he took me with him. I fondly recall the men in the choir secretly handing me candies during practice. My father was not only a superb tenor, he also collected Yiddish and Hebrew songs. Once he heard a song, he was, remarkably, able to write it down, note for note, in the same way most people are able to write words. Over time, he amassed a large collection of popular songs that he kept in a notebook. My father used to come home with new stories (by Shalom Aleichem and others) or poems, which he recited to us. I remember one of those poems, “Der Becher” (The Cup, by Simon Frug), very well. I was about six years old when I heard it. It went like this:¹

Tell me, Mother, is it true,

Grandfather used to say,

That a cup stands by God’s Throne

Since the First Day,

And whenever we suffer,

When our enemies eat us up,

God sheds a tear — Mother, God weeps!

And the tears fall in the cup.

One day, do you know, Mother,

When the cup is full of tears,

The redeemer of the world will come,

For whom we pray all these years….

This was the pivotal point at which I began to doubt the existence of a god. Why, if there is a god, does he need tears? Does he enjoy the pain? Is he a sadistic entity?

I was an inquisitive child and made it a point to speak my mind as soon as I was able to. There lived on the floor below us a lady whose name I can vaguely recall as Mrs. Kranzler. I remember she had white hair. True to my nature, I quizzically posed the question to my mother as to why this lady had clean hair and my mother’s hair was black, and therefore dirty. But, despite being an outspoken child, I never vocalized my doubt in God to my parents, perhaps because I knew they would not even entertain the idea that their beloved little one was thinking such thoughts. I kept my thoughts in my headstrong mind.

I went with my mother when she registered Chava in kindergarten. I tried to crawl under the benches so that I could join her. Sometime later, Chava became very ill. Four doctors were unable to diagnose what she had. It was only the fifth who realized that Chava had pleurisy. By the time she was taken to hospital, it was too late. She died on the operating table. I cannot recall Chava’s age at the time, but I have a vivid recollection of the chevre kedishe (burial society) coming to administer her burial rites.

***

Young as I was, I knew that many people, both Jewish and non-Jewish, began to leave Germany and Austria to settle in Belgium. Many of them settled in Antwerp. It was in this wave of migration that my father’s cousin Mendel arrived. He was about sixteen or seventeen years of age and had been sent by his parents, Moishe (my grandmother’s brother) and Gita, to look for an apartment. Was he able to decipher the gravity of the situation in Germany, or was he merely a carefree teenager? I recall that he played the harmonica especially well. He stayed with us for a short time, and he taught me German songs, one of which stuck in my head because of subsequent events: “Wenn die Soldaten durch die Stadt marschieren” (When the soldiers march through the city). He also had a collection of cards depicting soldiers in tanks and in battle. They looked foreboding, and it gave me an unsettling feeling to see them.

Soon after, Mendel’s parents arrived with his two younger brothers, Pinchas and Shmuel, and his young sister Dvorah, who was just two months younger than I was. Moishe was a shoychet (ritual slaughterer), and they were all extremely religious, except for Mendel. When my little sister Sara first saw black-bearded Moishe with his black clothes, she screamed. His appearance startled her. On Saturdays, our family would walk on over to their home and would sometimes stay for the Havdalah ceremony at the end of Shabbat. Dvorah and her mother would sometimes visit so that Dvorah and I could play together. Dvorah would playfully instruct me on all the things that one was not allowed to do on the Shabbat. I remember one occasion where her mother, Gita, once removed her hair and I saw her clean-shaven head. A wig!

Later on, a father and son who were fleeing Germany stayed with us. I vaguely recall their name being Perlmutter. One of Gita’s brothers and his son had also fled Germany. These refugees told horror stories about people who were sent to camps. They also told us about how Germans forced them to carry bags of sugar and made the Jewish prisoners lick the sugar that happened to spill onto the muddy ground.

Apart from the arrival of these refugees, both Jewish and gentile, there were distinct changes in daily life in Antwerp — a completely different atmosphere prevailed over my family’s daily goings-on. Jewish citizens were now barred from certain public places. When I was in Grade 4, I was switched to a different school. I was not told exactly why, but it became necessary for me to leave the school I was in.

[1] The source of this translation from Yiddish is unknown.

Escape to France

It was May 10, 1940, when the Germans entered Belgium. I remember hearing in the distance what I thought was thunder and my father suddenly waking up my sister Sara and me. The deep bellowing sound was not thunder. It was caused by bombs making contact with their targets. My father told us to quickly go down to the basement. The house where we lived had a cellar in which there were some bunk-bed-like structures. We slept on those, returning upstairs during the day. Sometimes, a siren would blare, signalling the need for us to retreat into the cellar for safety. Once, before going down, I looked out the window and saw an airplane, perhaps German, streaking across the dark sky, which was sparkling with stars, and proclaimed audibly and indignantly, “You are not going to scare me!” Whenever I see a night sky strongly resembling that one, I recall that moment. I was not scared then, but I was extremely worried. Having heard the horror stories from refugees who had fled Germany and Austria for Belgium, I wondered what would befall us.

At exactly what date our family and three other families left Antwerp toward France, I do not remember. We stopped in Ghent and a town called La Panne. In the city square, there were billboards with lists of refugees. A town crier walked about, boisterously making proclamations I never was able to decipher.

In La Panne, all the Jewish men were arrested. Sometime later, they were released. It wasn’t till some years ago that I heard from the daughter of one of the families who had been with us and survived the Shoah (Holocaust) that those men were arrested because they were believed to be spies. The phylacteries (tefillin) that they used in prayers were mistaken for some kind of radio transmitter.

A few days after that, we, together with another three families, took a cab and went to the train station, where we all boarded a train. We travelled all the way down to the foot of the Pyrenees to a town called Luchon. We were assigned a place to stay in a big house with an inside courtyard on rue Hortense 16, where each of us had a room.

Luchon was a very beautiful town with many spas and mineral springs, and people would come to indulge in the waters. We arrived at the end of May or beginning of June, and the street where we lived was lined with many rose bushes. Day in and day out, transports arrived along the main road, bearing maimed soldiers who were missing an arm or leg or two, with heads bandaged, their ears and other body parts lost in combat. The contrast between beautifully lavish Luchon and these mishaps of war has never left my memory.

There was a Polish brigade in France at the time. My father, having been born in Poland, was ordered to present himself for service. When the Germans continued to advance, the company my father was in was routed. In the confusion, people tried to escape. One morning, at around four o’clock, my mother woke me up so that I could see that my father had returned. I was so happy and relieved, I cried. Father told us that he had lost his tefillin while jumping onto the last train as he was fleeing. He was extremely upset. I didn’t understand the extent of his emotion until many years later, when I was in Israel. My father’s brother, who had survived in Siberia with his mother and sister, told me that my grandfather Yosef Hersh Herzel (who died of hunger in Siberia) was a chazan, a cantor, as well as a sofer stam (scribe) who wrote the documents that are placed in tefillin and mezuzot. I realized then that the tefillin that my father lost were more than a mere religious loss, but also possibly the loss of his father’s hard work.

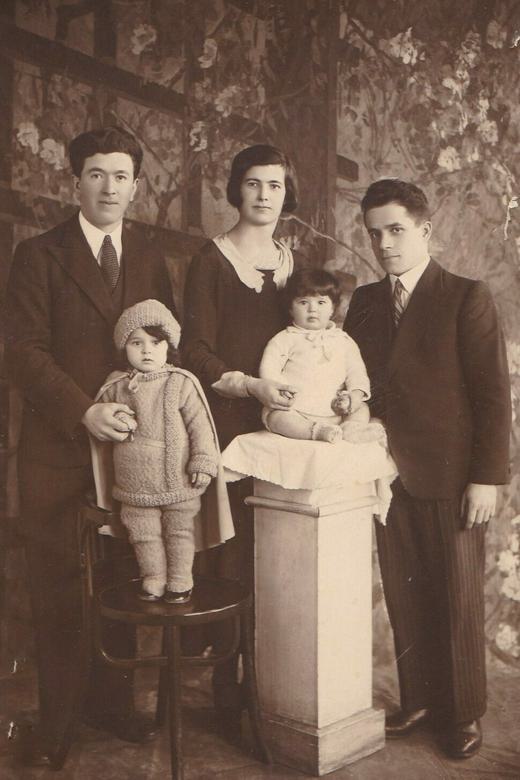

Bracha (front, far left) beside her sister, Sara, with a group of child refugees in Luchon (Bagnères-de-Luchon). France, 1940.

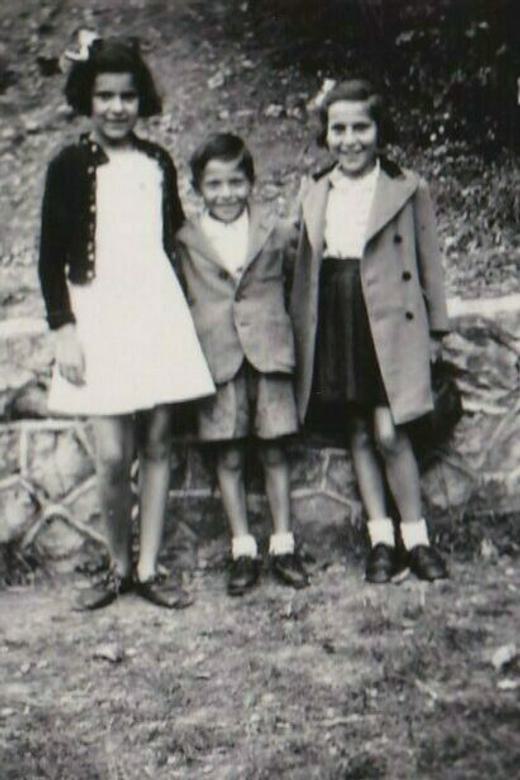

Bracha (left) with her friend Bella (right) and Bella’s brother (centre) before Bracha’s departure from the children’s home in Faverges. France, 1943.

From the sick room, I could see a road, and I used to walk to the window and stand there, wishing with all my might that I would see my parents and Sara walking toward the children’s home to come collect me.

The Last Letter

A short time later, I started having problems breathing. The doctor told my father that I was studying too hard for exams. I did not agree since I loved the challenge of exams. My parents decided (following the doctor’s advice) to send me to a children’s home run by the Swiss Red Cross - Children’s Aid. It was in Faverges at the border of Switzerland. If I am right, this decision was made not because of my illness but in order to save my life.

The home was in a grand fourth century castle. The ascent to the castle had to be made up the side of a mountain on wide steps. The children were housed in what had probably been the servants’ quarters, with five or six to a room. About a dozen or so of the eighty children there were Jewish. All children were sent there for only three months. After three months, they were sent home and another group was brought in for three months. Children from other parts of France were also sent to this home, not only to recuperate, but also because their families didn’t have enough food to feed them. The Jewish children were permitted to remain in the home for longer. However, in May 1943, Jewish children who still had parents living in France were sent home. I know a brother and sister who were sent back home from Faverges and managed to survive. When I met them after the war in Israel, they told me that the mayor of their town did not allow any Jews to be arrested and consequently Jews from that town were not sent to the concentration camps. The mayor had argued that the local Jewish population was working and providing services of one kind or another that allowed troops to be properly housed and fed. If such a valuable human resource were to be taken away, there was no way troops could be properly housed and fed. I’ve often thought that the mayors of other towns in France could have done and said the same thing.

In the last letter that I received from my father when he was in the detention camp called Le Vernet, he said that he was trying to get my little sister Sara to join me at Faverges. He did not succeed with this request to the authorities. Exactly why this was the case, I will never know, as there were siblings from the same family there in the facility with me. My sister was only seven and a half years old. At this point she had already been so traumatized. When I think about her and what happened to her, I can’t fathom the utter dread she would have experienced at the inhumane treatment that prisoners of these camps were subjected to hourly.

In Faverges I had been handed my father’s letter as we were sitting down to lunch. In it, my father told me that he, my mother and Sara had been arrested and taken to Le Vernet. Being the pragmatist that he was, my father went on to say that he did not know if we would ever see each other again. Years later, I found out that my little sister was sent to Auschwitz in convoy number 28 together with my parents and other relatives. This is the last I know of what happened to them.

I don’t know if the counsellors read that letter before it was handed to me. When I read it, I fell apart from a profound sadness and cried inconsolably for two months until I became very ill. I kept hiding under my bed. The doctor’s wife came to talk to me and tried to console me, but it was fruitless. I became so ill with a fever and headaches that they had to send me to the sick room. From the sick room, I could see a road, and I used to walk to the window and stand there, wishing with all my might that I would see my parents and Sara walking toward the children’s home to come collect me. I sensed that this desire was in vain, so above all else I wished to lose my mind so that I would not ache from wanting so badly to see my family again.

After two weeks, the nurse, Mademoiselle Zita Gossner, thought that I was well enough to go out to the courtyard, which had a playground with swing sets, a see-saw and so on. However, looking at the swings, I got dizzy. I walked to the door of the home, and just as I got there, I almost fainted and was assisted by the nurse, who just happened to be on her way out. I was in isolation for six weeks following that fainting spell. I ended up staying at that children’s home for around thirteen months.

The first director of the home, Mademoiselle Malotte, was considered incompetent and was dismissed. She would cut the girls’ hair vehemently, literally chopped off their hair. She also didn’t feed the children with care. The children’s home had counsellors who came from Switzerland to help supervise, feed and assist the children with whatever was necessary. One of those counsellors, Sina Jecklin, who had originally been hired as a cook, was a trained childcare worker and eventually rose to become the new director. She was an incredible woman. She later told me that she and other staff members would sometimes steal potatoes to feed the children. One Swiss counsellor, Monsieur Giannini, also introduced music and theatre as a way to include all the children and create some joy for them. For me it was therapeutic and helped me cope with the loss of my family. Mr. Giannini played the piano and taught us songs and directed us in plays such as Molière’s L’Avare (The Miser). I played the valet. My best friend from Faverges, with whom I am still in touch, Bella, played the role of the miser. The arts had always been an important part of my previously happy life, and they continued to be of great comfort to me and ultimately prevented me from losing my sanity with grief. Monsieur Giannini’s piano playing and songs really saved me.

The children from the Faverges home were often taken for hikes in the surrounding hills and mountains, and we went to school in the village. Once, we were walking along a path on the way to school or on a hike when a woman walked by and pointed at me. She asked the counsellor, Where did you get her from?

One day Rosa and I were put in a sick room. When I asked the reason for this, Mademoiselle Gossner told me that we had some infection in our eyes that was contagious. Of all the children in Faverges, only the two Jewish children, Rosa and I, developed this eye infection? It occurs to me now that a counsellor who went with us must have heard the comment of the woman on the path, and that’s why Rosa and I were put in the sickroom. Did that woman tell the authorities of Faverges that she thought there were Jewish children in the children’s home? Was this also the reason that the staff at Faverges decided to get Rosa and me out of the home?