Ann Wigoda

Born: Berlin, Germany, 1932

Wartime experience: Escape, hiding

Writing Partner: Jane Szilvassy

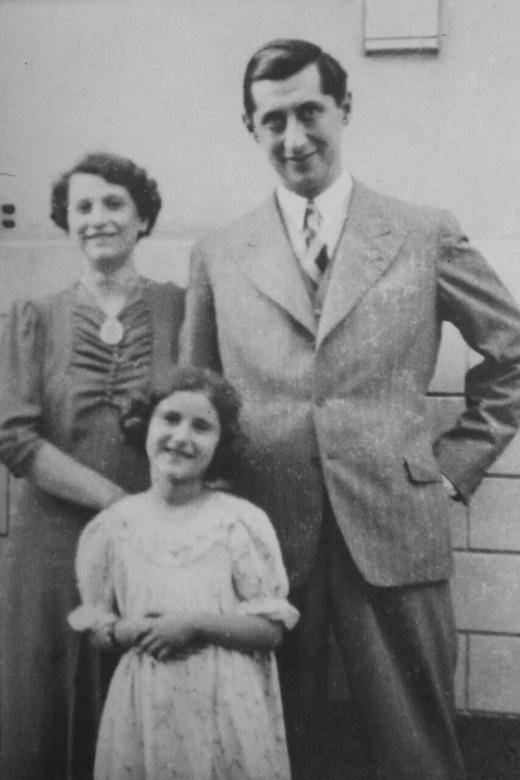

Ann Wigoda (née Mendelsohn) was born in Berlin, Germany, in 1932 and immigrated illegally to Belgium with her parents in 1938. After the German occupation of Belgium, her father was arrested as a German national and sent to internment camps in France.

He was eventually deported from France to camps in Poland and Germany, and he died in Buchenwald in 1945. Ann hid with her mother in various homes of non-Jews before she was separated from her mother and hidden in orphanages and convents with the help of Belgian resistance organizations. In 1949, Ann and her mother immigrated to Israel. Ann met and married her husband, Morris, in Israel in 1951, and they had two children before immigrating to Canada in 1959 and settling in Toronto, where Ann worked as a dressmaker. Ann Wigoda passed away in 2025.

Flight to Belgium

My childhood was normal until 1938. We lived in Berlin at Dolziger Strasse 39, not too far from Alexanderplatz. Our building was part of a block of four houses that had a courtyard in the middle. An attic connected all four buildings and served as a washhouse for the tenants.

There was a church nearby, and when there was a wedding, I liked to watch the couples arriving by horse-drawn carriage. It was a big attraction for me as a child. There was a garden close by as well, and I used to play there. I remember children would jump on the ice wagons as they passed in the streets.

We were a traditional family. My mother kept kosher. She lit the Shabbat candles every Friday night, and my father made Kiddush. My parents fasted on Yom Kippur and went to the synagogue for High Holiday services. Even though the country was in a depression, I was not deprived of anything.

My parents had a busy social life. There were many big gatherings with friends and relatives, in our apartment and theirs, and we frequently visited some cousins of my mother who lived nearby. The main sources of entertainment, beside lively conversation, were playing the piano, listening to music on the radio and, for the men, playing cards.

I absolutely adored my father. He was tall and handsome, slim with brown hair and big brown eyes. To me, he was like a movie star. Just picture Cary Grant; this is who he resembled in my eyes. And as an only child, I got all his attention. He was my playmate. We played store and school together. We made the food items out of multicoloured plasticine, and I can still picture him standing tall in a corner, being punished by me for misbehaving! I loved accompanying my father when he went to work in the mornings. He would buy me goodies from the street-corner candy dispenser and then send me back home to my mother.

Ours was a happy life until 1938. Then I began to be personally affected by what was happening in Germany. By then, the Nazis’ reign of terror was in full swing, and more and more Jewish men were being arrested and put into concentration camps. My father did not feel safe anymore and opted to leave the country clandestinely. He arrived safely in Brussels, Belgium, on April 27, 1938.

Neighbours who had fussed over me started to avoid me. Instead of welcoming me into their apartments as they used to, they slammed their doors when I came to visit. I was so hurt. I did not understand. When I think about it now, I realize it had probably become dangerous for them to have relationships with Jews.

I once fell in our vestibule in front of two women who were talking to each other. I was bleeding, but they looked the other way and just ignored me while I was crying and struggling to get up. On the street, the children started to goad me into fights and tease me, chanting, “Our blood is sweet, and your blood is sour.” I would run to my mother and ask her why I was a Jew. It felt like being cursed. I remember being sent to buy milk and being attacked by some children who made me spill it. Another time, I had bought candies, and some children grabbed them away from me.

I had a doll that was very special to me; she could open and close her eyes. One day, I went out to play with it, and some children took hold of her and dropped her into a puddle; they surrounded me and prevented me from retrieving her. Finally, they left me alone, but by then the doll’s eyes had sunk into her head. I ran upstairs crying, but there was nothing to be done anymore. Only when my mother’s friend Meta came to visit with her two older boys and we went out to play together did I feel safe on the street, as I was protected by them.

I did not go to kindergarten, but I was looking forward to my sixth birthday and my first day of school because it was the custom for children to be given a big coronet filled with all kinds of goodies on that day. But it was not to be. We left Germany at the end of June 1938, just before the start of the school year.

***

Right after his arrival in Belgium, my father had started to make plans to smuggle us out of Germany to join him in Brussels. In the meantime, my maternal grandmother died of a major stroke on June 20, 1938. My mother was able to secure a Certificate of Good Conduct, which was necessary for us to travel outside of Germany. The certificate arrived too late for us to attend the funeral, but it enabled us to take the train part of the way out of the country. When we reached the guide my father had hired to lead us the rest of the way out of Germany, there were more people with children waiting there.

We travelled in two groups, mostly by night and through forests. I was not put in my mother’s group, which was a terrifying experience for me, and the first of many separations. Eventually my group arrived at the farm where we were to spend the night. My mother’s group was not there yet. I panicked and cried and had to be calmed down with reassurances that my mother would soon show up, which she did. The children were offered beds, and the adults had to sleep in the barn on straw, but I could not be enticed to be separated from my mother again. She slept on the straw with me on top of her so that the straw would not prick me.

In the morning, we were given white bread for breakfast. I had never seen white bread before — I was used to the black bread we ate in Berlin — and I refused to eat it. Eventually, several cars arrived to take us to Cologne, where we spent the next night. From there, we went by train to Brussels, where my father was awaiting us at the station. The whole journey probably took two or three days, and we were all happily reunited on July 1, 1938.

My parents were conversing in German when a policeman overheard them and asked for my father’s papers. He was arrested on the spot as a German citizen — now an enemy! That day was the last time I saw my father.

Into Hiding

Our lives changed forever on May 10, 1940. My mother was in the hospital at the time (I never knew why). That morning, as my father was walking me to school, the church bells started to toll, announcing that Belgium had been invaded. My father turned around and took me to his workplace instead of to my school. The police were already there, calling out people’s names and arresting them. We managed to leave unseen, sneaking out through the back door. My father took me to my Polish friend Renee’s house and then went to visit my mother in the hospital. My parents were conversing in German when a policeman overheard them and asked for my father’s papers. He was arrested on the spot as a German citizen — now an enemy! That day was the last time I saw my father. I was seven years old, and my father was only thirty-eight.

That evening, two policemen came to pick me up at Renee’s house to take me to an orphanage. I have always wondered why her parents, who were friends of my parents, did not let me stay with them until my mother was released from the hospital. I never had a chance to ask them, as they were ultimately all deported and did not survive. I was crying and asking for my father, and the policemen assured me that he would be back soon. They sympathized with me and even stopped the car and bought me a chocolate bar. It was a kind gesture that I have never forgotten.

I stayed in the orphanage for probably only a few days, but to a small child separated from her parents, it seemed like an eternity. As soon as my mother was released from hospital, she came to pick me up and took me home. She explained to me that all German nationals and German sympathizers were being arrested without distinction as dangerous aliens of Belgium. The prisoners were incarcerated in improvised camps where they remained until they were either released or deported to the south of France. This became the fate of many German and Austrian Jews.

My parents corresponded after my father’s deportation to France. My mother and I waited eagerly for his letters; they were the highlight of our days! We constantly read and reread them. These letters had a great emotional impact on me, and some particularly moving parts were imprinted in my memory forever. I had a premonition that my father would escape to be back with us for my ninth birthday. I eventually found out that he actually tried to escape from the camp on August 13, 1941, and my birthday is August 23! Alas, he was not successful in his attempt to join us. His last letter reached us in the early fall of 1942.

***

By early summer 1942, deportations of the Jews were in full swing and my mother, with the help of an organization called Œuvre Nationale de l’Enfance (the National Organization for the Children) and a Jewish organization (possibly L’Aide aux Israélites Victimes de la Guerre, Aid to Jewish Victims of War or Comité de Défence des Juifs, Jewish Defense Committee), managed to have me hidden.

Andrée Geulen, a twenty-year-old schoolteacher, worked with the Comité de Défence des Juifs to save Jewish children. She personally transported three to four hundred children to safety. Altogether the group hid an estimated three to four thousand children, mainly in convents. To avoid detection if they were arrested by the Gestapo, they hid all their records in different locations in four notebooks of different colours. In one notebook they recorded the child’s false name and date of birth. In another one they recorded the name of the institution where the child was hidden. In a different one, they recorded the real name of the child, and in yet another, the number of each child. I am inscribed as number seventy-one.

In March of 2007, I went to Israel to attend a conference of Jews who had been hidden in Belgian as children during the war. Andrée Geulen was in attendance. She was honoured at Yad Vashem and given honorary Israeli citizenship. In her speech she said, “What I did was mainly my duty.”

I was first hidden in a teachers’ college while the teachers were on their summer vacation and then in a Jewish-run orphanage tolerated by the Germans. I believe that this orphanage was in Vlezenbeek, in the vicinity of Brussels. I was so miserable there that I told my mother I would run away if she did not take me home. She did. Children ran away from there all the time but were usually caught and returned. Then I was hidden in a huge convent in Chimay, near the French border. It was run by French nuns and was full of novitiates. It was here that I was given my false identity of Anna, with a typically French surname, Meunier. I was very unhappy there as the atmosphere was cold and unfriendly.

Finally, in the fall of 1943, I was sent to another convent. This convent was in Obourg, a small village near Mons. It was a boarding school administered by the Sisters of Saint Vincent de Paul. This institution was small and less formal, run by six young nuns and two middle-aged lay helpers. Sometimes the local children would tease me about my last name, Meunier (“miller” in French), and would surround me singing, “Meunier, tu dors, ton moulin va trop vite,” which translates as, “Miller, you are sleeping, your mill turns too fast.”

The gentile boarders were all from the region; only the Jewish boarders were from the capital, Brussels. There were at least a dozen of us, so they nicknamed us “les Bruxelloises.” We were different. During the summer vacations when the gentile children went home to their respective families, and we, the Jewish children, were the only ones left in the convent, the atmosphere became even more relaxed. Two of the nuns played classical music. Sister Louise, who was in charge of my age group, played the piano and sang while Sister Madeleine, who was our nurse, accompanied her on the violin. Sister Louise had a lovely voice and performed beautifully. She also had a good sense of humour. Though I was not unhappy there, I remained a lonely child and was more often than not submerged in books. I remained in Obourg until the end of the war.

My mother had not been told my whereabouts. The organizers feared that if she were to be arrested, she might come and take me with her. Many parents did in the early days, not wanting to leave their child behind, not suspecting their fates. This endangered the lives of the nuns and the other Jewish children who were hidden at the convent. After eight months of separation, my social worker, whom my mother had befriended, took pity on her and divulged my hiding place. I still recall the day I was told I had a visitor in the parlour waiting to see me and found my mother there. What an emotional reunion that was for the both of us!

When the situation became so untenable that my mother was afraid to stay in Brussels any longer, she asked Sister Helene, the head nun in my convent, if she could help her find a hiding place. She found her a place in a convent in Maisières, a mere four kilometres away. My mother worked there as a domestic for her keep and a small stipend. She was able to visit me regularly on her free Sundays, taking only the back roads as a precaution. With her meagre salary, she bought food from a family of farmers named Lorette to supplement my diet. This is how we were able to survive the war.

Ann in the convent in Obourg. Belgium, 1944. Courtesy of Crestwood Oral History Project.

Sister Louise, the nun who was in charge of Ann’s age group in the convent. Courtesy of Crestwood Oral History Project.

Back to Orphanages

Soon after the war, my mother suffered several nervous breakdowns. The privations and psychological anxieties and the unknown fate of my father had taken their toll on her psyche and physical health. I was given various reasons for her stays in the hospitals, only learning the truth much later.

Due to my mother’s breakdowns, I was sent to at least three orphanages in Brussels. Two of them were Jewish establishments and one was the place I had been sent to after my father’s arrest in Brussels. These were short stays, probably only a couple of months each, but in Mariaburg (Sint-Mariaburg), a suburb of Antwerp, I stayed for a whole year.

The orphanage in Mariaburg made a lasting impression on me. It was run by a German Jewish Orthodox family, Mr. Jonas Tiefenbrunner and his wife, Ruth. We were about twenty to thirty children living in a large villa. The children were either survivors of concentration camps or orphans who had been in hiding during the war. I was very happy there as it had a familiar atmosphere, and Mr. Tiefenbrunner was a surrogate father to us all. This couple had a three-year-old girl named Jeannette, and their daughter Judith was born while I was there. I was among the oldest children and slept in a room with three other girls. Every night I told them stories I had either read or invented. When I later lived in Israel, Mr. Tiefenbrunner called on me while he was on a visit and honoured me by having dinner at my place! I corresponded with him until his death of a heart attack in 1962. He was a mere sixty-two years old. Over the years, I was also able to reconnect with some of the girls who were in the orphanage with me.

I remember a few episodes of my time in Mariaburg. We used to take daily walks, and once we passed a small statue of a saint. We started stuffing grass in the statue’s mouth and laughing, but were reprimanded by Mr. Tiefenbrunner, who told us that one must show respect toward all religions — a lesson I have never forgotten. Another time, right in the middle of winter, we had snow practically up to our knees, and we were marched to a refugee camp full of women who had survived concentration camps. I shall never forget how we were embraced by these women and how they cried. I never knew for sure if they wept because they were thinking of their own children who had perished, or if those were tears of joy because they were so happy to see that, after all, Jewish children had survived the war. It might have been a mixture of both.

Ann (back row, far left) with her Grade 6 class in Brussels after the war. Belgium, circa 1945. Courtesy of Crestwood Oral History Project.

Ann (second from the left) at the orphanage run by Jonas and Ruth Tiefenbrunner. Sint-Mariaburg, Belgium, circa 1946. Courtesy of Crestwood Oral History Project.

Adjustments in Canada

When I was in Brussels, I had attended a private high school where half the day was for academic studies and the other half was spent learning dressmaking. In Toronto, I had some customers for whom I made dresses, but very few. People wanted to see my work before they would order, but how could I show them my work if they didn’t give me any? It was difficult trying to get started.

I also had personal problems adjusting to all the changes in my life. I felt very isolated, I missed my extended family with whom I had been very close, and I missed my social life in Israel. I had no close friends but needed to unburden myself. I sought help at a psychology clinic on Queen Street West, and my social worker, Joan Stewart, was so helpful in getting my sewing career started. She gave me work and she sent her colleagues to me. They were all delighted with what I did for them. Now I had something to show to my Jewish acquaintances, who were not the ones to give me a break at that time. Suddenly I had clients galore who wanted me to sew their gowns, dresses and suits. They were proud to have me as their dressmaker. In the beginning, some women tried to give me a hard time, such as expecting me to charge less for making a cotton dress, which involved the same amount of work as one made from a more expensive fabric. After a while, I was able to pick and choose my clients and name my price. A cousin of my mother’s, who was a corset maker in the Netherlands, had advised me to never let my clients bargain and to stick to my price, and that is what I did. Since I worked from home, I was always there for my children when they came home for lunch. I arranged my clients’ appointments to fit this schedule, and if a client happened to come early, she waited patiently until the children went back to school. I also took the summers off to be with my children during the summer break.

It was around this time that I discovered the public libraries with their huge selection of books. This was so exhilarating to me because I had always been such an avid reader.

My mother came often to visit us in Canada, and one of her visits was for our son’s bar mitzvah. That was in 1971, and she stayed with us for ten months but eventually decided to go back to Berlin. Her nerves were fragile, and the children were young and very noisy. She did not speak English and did not know her way around. It is always very difficult for an older person to be uprooted.

***

My mother’s last Toronto visit was for our daughter’s wedding in 1975. She passed away in Berlin on October 23, 1977. I was visiting her at the time, and my husband, Morris, came to her funeral.

While sorting out my mother’s affairs after her death, I had the good luck to find my father’s correspondence to her. Unbeknownst to me, she had kept his letters, but I was not able to decipher them. His writing was small and dense because paper was scarce for him. His handwriting was difficult for me to read because I am not familiar with the German alphabet, but one day it occurred to me to ask my German friend Renate, whom I had known for twenty years, if she could transcribe them for me. She told me she would be honoured to do so. She could not read everything either, but she did her best. She worked on it from morning to night for two months and told me it had become an obsession for her. She typed up the letters and even helped me translate them into English. If not for Renate’s keen interest and effort, I still would not know the contents of my father’s correspondence.

It is quite obvious to me that my parents had a secret code between them because some of my father’s writing is not clear to me. My father often refers to people as “Aunt” and “Uncle,” but this does not mean that they were our relatives; German children often refer to adults that way, which further complicated the meaning of his letters. I know that “Uncle Kissi” was an indirect reference to himself. Kissi was his nickname. I even have in my possession a photo that he sent his brother, Moritz. The back of it is dated July 1930, and it is signed, “Kissi und Betty” (Betty was my mother). Reading my father’s letters helps me realize the amazingly deep faith he had in God. He somehow knew about and observed all the Jewish holidays while in the camps, and despite his starvation diet, he fasted on Yom Kippur! He kept his faith up to the time of his deportation to Drancy. His last written words were “God help us.”