Stories of Pesach: Holocaust Survivors Remember

As I started to write this memoir, spring was approaching, and with it, the holiday of Pesach, or Passover. I don’t remember everything from my childhood, but some things, like the Passover holiday, were so special that the memories are very clear to me.

George Stern, Vanished Boyhood

Pesach, or Passover in English, often figures prominently in the stories of authors who survived the Holocaust as children. Introduced at an early age to the cultural and religious traditions of this celebration, the authors share the customs and flavours associated with these happy childhood experiences, memories that are both joyful and nostalgic.

The following excerpts from our books illustrate how Pesach was celebrated across Europe before the war. The depictions testify to both a common cultural identity as well as the great diversity of Jewish communities. The excerpts also show that many Jews continued to celebrate Pesach even during the Holocaust, sometimes in precarious conditions — celebrating their Jewish identity and resisting discrimination and persecution.

Pesach remains a time of celebration for our authors, an opportunity to continue family traditions in the country that welcomed them after World War II.

Pesach, a celebration of traditions

Pesach commemorates the liberation and exodus of the Israelite slaves from Egypt during the reign of the Pharaoh Ramses II. The spring festival lasts for eight days and begins with a lavish ritual meal called a seder on the first two nights. During the seder, the story of Exodus is retold through the reading of a Jewish religious text called a Haggadah. With its special foods, songs, and customs, the seder is the focal point of the Passover celebration and is traditionally a time of family gathering.

During Pesach, Jews refrain from eating chametz — anything that contains barley, wheat, rye, oats or spelt that has undergone fermentation as a result of contact with liquid. Avoiding chametz commemorates the escape from Egypt, when Jews did not have time to let their bread rise. Before Pesach, Jews also clean their homes to remove these foods, as well as anything that has been in contact with them. Separate dishes that have never been in contact with chametz are used only for Pesach.

Born in 1931 in Paris, France, Muguette Myers recounts in her memoir, Where Courage Lives, the different Pesach traditions of her childhood. Her maternal grandparents, the Fiszmans, were very religious, but her paternal grandparents, the Szpajzers, were non-practising, which sometimes gave rise to funny situations during Pesach.

“At Pesach, or Passover, all vestiges of non-Passover food, even crumbs, have to be searched for and removed from cupboards. All dishes have to be changed for Passover dishes. While the Fiszman household was busy cleaning, the Szpajzer couldn’t have cared less. One Pesach, it just so happened that Gromeh [grandmother] Fiszman came to visit the Szpajzers. Their windows looked out on the courtyard and they could see Gromeh making her way to their apartment. Gromeh Szpajzer ran to a neighbour who was as non-practising as she was and they quickly exchanged kettles as well as several cups, saucers, forks and spoons so Gromeh Fiszman would think that the dishes had been changed.”

Muguette also has excellent memories of the Jewish culinary specialties she enjoyed during Pesach:

“When Passover came we had matzot [crisp flatbread made of plain white flour and water that is not allowed to rise before or during baking], chicken soup with matzo balls, and gefilte fish [a dish generally made from chopped whitefish that is made into patties and boiled]. Gromeh also made her own raisin wine for Pesach, a process she started right after the Rosh Hashanah holiday. She let it ferment and then filtered it; then she let it rest another month and did the filtering again. She repeated this process about three more times before the wine was ready for consumption. I loved this wine. When I stayed with her and whenever visitors came, I was allowed a very small glass at mealtime.”

George Stern describes in Vanished Boyhood the kosher wines that his family donated to the less fortunate of Jews of Újpest, Hungary, on Passover:

“One Passover tradition asks that if people can afford to, they provide those less fortunate with foods that are eaten during the holiday, like matzah, eggs, chicken or wine. My father, Ernő and Uncle Jenő kept that tradition by putting aside one barrel of kosher wine from their vineyard. Just before Passover, poor families could come to our courtyard, where our wine store was located and collect as much wine as they needed. When I was eight years old, I was eight years old, I was given the honour of giving out the wine to them and I filled the bottles they brought, one by one. This took almost the whole day because we gave away a few hundred litres of wine, but I was glad to do it because it was a mitzvah, a good deed.”

Although she also attaches great importance to food, Ann Szedlecki emphasizes the other annual customs of Passover in the Jewish quarter of Lodz, Poland. Her memoir, Album of My Life, describes Ann’s last family seder before the war.

“In the spring of 1939 the annual rites of the season began as they did every year when the housewives dumped the old straw from the mattresses and replaced it with fresh smelling straw. This meant that Passover couldn’t be far off.

For Passover, I was always outfitted with new clothing — new ribbons for my braids, new underwear and socks, a dress and new shoes.

[…]

Preparations for Passover could be seen and felt everywhere. The wooden floor of our kitchen — which was where my father worked as well as where my mother cooked — was scoured with sand to get out the oil stains left by the sewing machines. Red wax was applied to the floor and allowed to dry, Finally, a heavy polisher was pushed manually across the floor to give it a shine. My mother distilled homemade wine, drop after drop running through clean linen, leaving a deposit. The linen was changed few times until the wine was clear. She also prepared a large jar of cut-up red beets and water — the water would ferment and be used in place of vinegar, which wasn’t allowed because it is a product of wheat, or chametz, which is forbidden on Passover, and the beets were used for our borsht (beet soup). Our large laundry basket, by now well scrubbed and lined with a large white sheet, was ready to store the matzah (unleavened bread). We had special Passover dishes and cutlery, but we didn’t have a Passover set of pots and pans so our everyday set was made kosher by a man who pulled a wagon containing metal vats with hot water. After the pots and pans were dipped in the water, the cookware was declared kosher for Passover.

After all these preparations, we followed our father through the house on the evening before Passover. With candles in our hands — he held a feather — we went through every corner to get out the last bits of chametz trapped in the crevices. We would follow the traditions of burning any last chametz we found the next morning.

By noon the next day, everything was ready for the festivities. The beautifully ironed white tablecloth, the polished sterling silver candlesticks, the arm chair where my father would sit leaning on a huge pillow at the first seder that evening. On the table were china, cutlery napkins, wine glasses and a plate of matzah covered with a beautifully embroidered cover set before my father’s seat. A traditional round seder plate held a roasted egg, a shank bone, bitter herbs and so on. Mouth-watering smells emanated from the kitchen all afternoon. My stomach growled, but it would have to wait. My sister, her husband and the baby soon arrived. There were six adults, but only four chairs. The lounge was put against the table for me and my brother, Shoel.

The seder began when the women lit the candles, said the blessings and the Haggadot [a book of readings followed at the Passover seder service] were opened. My brother asked the Four Questions, even though I was the youngest (except for the baby). I checked Elijah’s cup to see if he had drunk from it. The seder prayers and readings went smoothly until we reached the song ‘Dayenu’ [a traditional song of gratitude that is sung during the rituel meal, or seder]. As long as I could remember I always giggled when I heard this song. This year, I was almost fourteen years old and an aunt and I hoped that I had outgrown the laughing. No such luck. As we got closer to singing ‘Dayenu’ my father’s blue eyes beneath bushy black brows fixed on me as if asking to behave. I got up from the table, my hand over my mouth, and when I reached the kitchen the giggles I was holding back erupted.”

Pesach under the Anti-Jewish Nazi Legislation (During the Holocaust)

Pesach traditions were shattered by the Nazis’ antisemitic laws. The Nazis orchestrated the annihilation of the Jewish population of Europe and, consequently, the systematic destruction of Jewish cultural and religious heritage. Despite this oppression, Jews strove to maintain the practice of their customs and rituals, to preserve their human dignity and identity. The following excerpts illustrate how, during the Holocaust, Pesach celebrations gave rise to a form of spiritual resistance, even in the most difficult circumstances.

On April 19, 1943, the first night of Pesach, Warsaw ghetto resistance fighters attacked German soldiers in a revolt, better known as the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. Seeking refuge in a secret underground shelter, Pinchas Gutter’s family made a seder, seeking to find, through this ritual, peace and comfort.

“We existed … by hiding, until April 19, 1943, Erev Pesach, the eve of Passover, which was also the eve of the uprising of the Warsaw ghetto. That day, there was an alarm. The few telephones that existed in the ghetto were still somehow working — these were mostly in apartments where doctors or other people deemed important lived — and the Polish underground resistance on the outside who were working with the Jewish underground phoned someone in the ghetto to say that the Nazis were coming in to take everybody out. By that time, there were already lots of bunkers in the ghetto. We had also prepared a bunker underneath the ruins at the front of our building. The caretaker and the men in our building, including my father, had dug it out, creating a middle section as an entrance and a room on either side. They didn’t want to give up and be taken by the Germans and so they put in food, electricity and water and air vents so the bunker couldn’t be discerned from the outside. My father and mother prepared us children for when we would have to go there. They told us that when the time came to go into the bunker, we were to ask no questions and we must get ready as quickly as we could.

That day, we all went down to the bunker, about 150 people in all. … My father must have brought wine, somebody else had matzos, and that evening in the bunker, they made a seder. Everyone was crying and praying. These were religious Jews who knew by heart the Haggadah, the Jewish text that sets forth the order of the Passover seder, and it still amazes me that, at such a dire time, they never forgot their culture and their morals. They also always made sure to shelter and look after their children.” – Pinchas Gutter, Memories in Focus

“In April 1942 we had twenty-two Jewish partisans in our group. Because we had all lost our own families, we felt like a family — we became brothers and sisters to one another. One of the Jews in our group, Moishe Abramowitz, who had escaped from the town of Bobruisk, had brought with him a small prayer book that he kept hidden in his boots. He helped our group cope with the difficult conditions in the forest and the tragedy of our people. Reminding us that Passover was fast approaching, he managed to obtain some beets to make a red soup to substitute for wine, traditionally used during the holiday ritual. We had no matzah, but he dug up some horseradish from nearby fields. On the night of the first seder, we gathered near our underground bunker.

As I was the youngest, it was decided that I would ask the Four Questions, the Ma Nishtanah. I knew them well since, as the youngest in my family, I had always been the appropriate candidate. Here in the forest I interpreted the answers to the questions somewhat differently. In answer to the question, ‘Why is this night different from all other nights?’ I replied, ‘Because last Passover all the Jews sat with their families at tables beautifully set with matzah and goblets of red wine. Last year, each of us had a goblet on our plate and listened to the oldest person in our household conduct the seder. Tonight, in the forest, our lonely and orphaned group, having miraculously survived, remembers our loved ones who were taken from us forever.’ Tears fell from our eyes. After this, we continued to keep the traditions of all the Jewish holidays, which gave us the courage and the will to survive. With God’s help, we would eventually live in this world as free people.” - Michael Kutz, If, by miracle

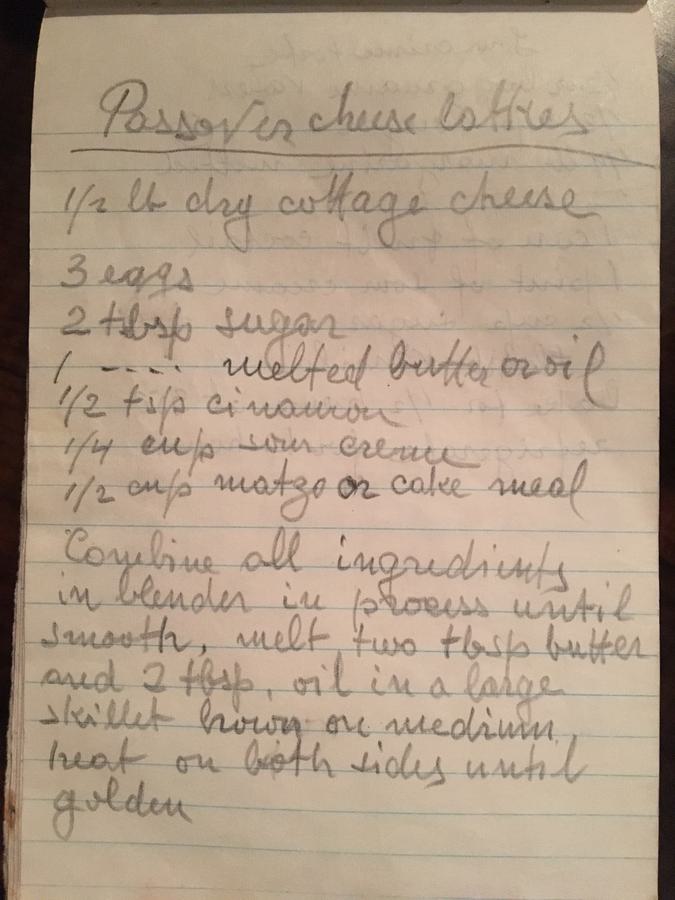

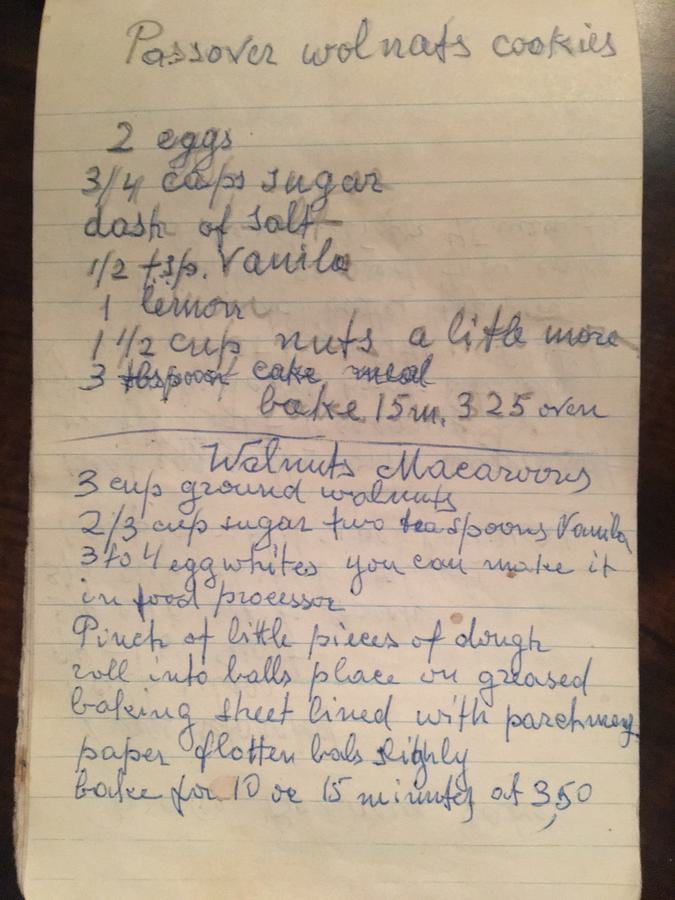

Pesach in Canada

Muguette Myers was in hiding with her family during the Holocaust. In 1947, she immigrated to Canada. Today, although she is non-practicing, she enjoys celebrating Pesach with her children, her grandchildren and her great-granddaughter. She enjoys the traditional Jewish dishes prepared by her daughter, who sustains the culinary and religious heritage of her grandparents, the Fiszmans. Muguette also treasures the traditional recipes of her childhood, written by hand by her mother, which she generously agreed to share in this article.