Cholent: Tasting the Past

Reading the memoirs of Holocaust survivors can be difficult and emotional. Our authors not only describe the tragedies and despairs of suffering and surviving, but they also reminisce about the pre-war Jewish life that was lost in their hometowns. They write about daily life and culture in their villages, towns and cities, from the mundane to the rituals to the food they used to eat. Reading about the food is one of my favourite parts of the memoirs that we publish — how families celebrated the Jewish holidays and Sabbath, and how most of the memories of these joyous occasions are tied into what they ate. Food is not what most people think about when reading a memoir of a Holocaust survivor, yet I find these descriptions so important. I am interested not just because of how food and tradition universally unite people but because, as important as it is to remember how millions of Jews died, it is equally important to remember how they lived.

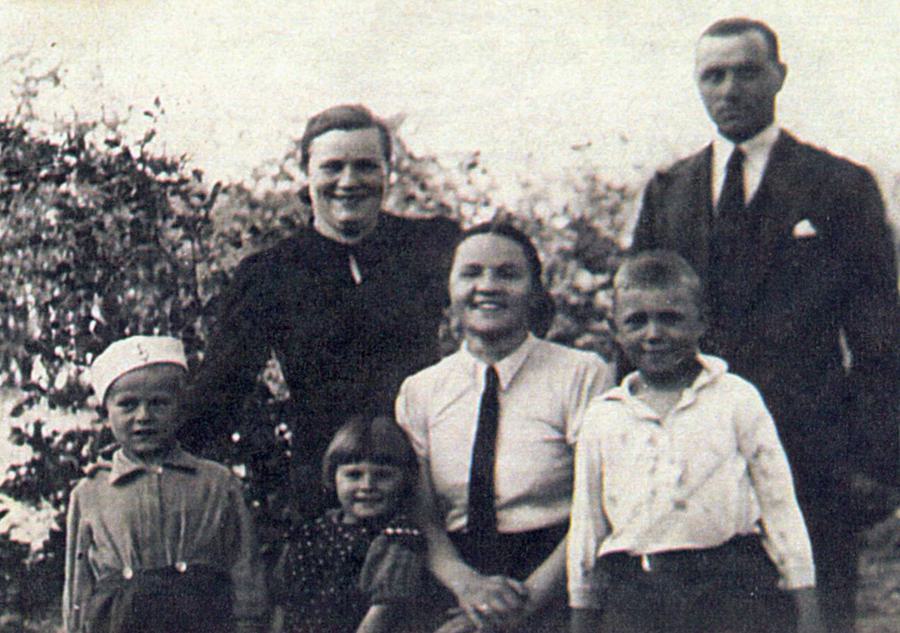

The descriptions of Bronia Beker’s aunt’s fresh-baked cinnamon rolls and the dense black bread and gefilte fish that Steve Rotschild’s grandmother would make in anticipation of the festive Shabbat meal make me salivate every time I read them.

I could easily write a blog post about many of the Jewish foods found in our memoirs, but the one food that seems to be both uniquely Jewish and distinctively personal to each author is cholent. Created to adhere to the prohibition of not cooking on the Sabbath, this stew would be prepared before sundown on Friday and simmer on low in an oven overnight so that the family could enjoy a hot meal on Saturday afternoon.

The method of cooking cholent hasn’t changed in 2,000 years, although the ingredients vary from country to country and over time. On Friday evening, a large clay pot is filled with layers of potatoes, beans, barley, meat and spices. The top of the pot is sealed with dough made of a mixture of flour, egg, water and melted chicken fat, and then covered with paper and tied with string. The pot is then put in a hot brick oven to cook slowly for twenty-four hours. The result is a delicious, hot, very aromatic meal.

- Steve Rotschild

According to food historian Gil Marks, the word cholent (with ‘ch’ pronounced as in ‘chair’) may have come from the French chaud-lent, meaning “warm slowly,” and, less likely, from the Yiddish shul ende, which describes when the cholent is eaten — at “synagogue end.”

Although nobody knows the exact source of the word “cholent,” the dish is without a doubt one of the most beloved Shabbat memories for our authors.

On Saturday, there was always cholent for the midday meal. My mother would prepare this bean and meat casserole on Fridays and take it to the bakery, where it would cook overnight in the oven. Then, after prayers the next day, my sister and I would run to the bakery to collect it. We had a little piece of paper with a number written on it that we would give to the baker and in return, he would give us my mother’s big pot of cholent. My sister would take one side and I would take the other and we would run home quickly because lunch needed to be served. As we ran, we anticipated the aroma and the delicious meat and barley, beans and potatoes; we also knew that nestled inside the cholent there was a little sealed ceramic pot with a sweet kugel for dessert.

– Pinchas Gutter

Even today, I hear people talk about the warm memories and feelings that a pot of cholent conjures. People have an emotional response to the word cholent — it may be a memory of a meal at their grandparents’ house, of kiddush after shul or of that unmistakable smell that warms the entire home on a cold winter morning. I totally relate to this emotional response even though I didn’t grow up eating cholent. Shabbat stews are cooked all over the world in different ways and under many different names. My Sephardic mother would make a similar dish called dafina, an iconic slow-cooked Moroccan stew with meat and potatoes but also with chickpeas, rice and eggs.

For the past decade, a more traditional Ashkenazi cholent has made a regular appearance on our Shabbat table thanks to my brother-in-law, who learned to make it while studying in yeshiva. My slow-cooker recipe has evolved over time to reflect my mixed Sephardic and Ashkenazi tastes. My current recipe is below.

Cholent recipes vary greatly from region to region, and even from family to family. No two cholent recipes are exactly alike. It’s one of those dishes that evolves over generations, with spices and ingredients being added or changed to suit family tastes.

Author Pinchas Gutter has adapted his traditional cholent recipe to accommodate his vegan family members. Pinchas shares his recipe here:

For many, food remains the anchor to our Jewish culture and forms an essential part of our collective memory that connects us to the story of the Jewish people. Long before there were “Instant Pots” and slow cooking became all the rage, we had cholent, cooked slowly in a hot, sealed oven. When we gather around a pot of cholent with friends and family, we bring a bit of the old shtetl world into our modern lives.

Jody’s Cholent Recipe

- 2 cups dried mixed beans

- 1 cup barley

- 2 cloves garlic, chopped

- 2 onions, chopped

- 2 lbs blade chuck steak, cut in thirds

- 6 potatoes, cut into chunks

- 3/4 cup ketchup

- 1 tbsp paprika

- 1 tsp black pepper

- 1 tbsp salt

- kishka (either vegetarian or meat)

- 6 whole Eggs

Optional ingredients:

- kishka (either vegetarian or meat)

- 6 whole eggs

Place all the ingredients, except for the optional ingredients, in the order listed in a slow cooker set on high and cover with water (or a can of beer and then water).

I recommend making this in the morning, and it will be ready to be eaten for lunch the next day. The total cooking time is about 26 hours. Give it a mix every few hours throughout the day if possible and then turn the slow cooker to low before Shabbat (sunset) and add the final optional ingredients, kishka and eggs.

Kishka used to refer to stuffed intestines, but it now refers to a tube of stuffing that can sometimes be vegetarian but is usually filled with meat, and can be purchased at any kosher butcher. Place the kishka across the top of the stew before turning the slow cooker to low.

Adding eggs is totally Moroccan-style. Leave whole eggs on the counter while you’re cooking the cholent so that the eggs will be room temperature by the time they are added. Pop them whole in their shells into the pot when you turn the slow cooker to low. At lunchtime the following day, take the eggs out and peel them and you’ll find they’ve turned brown and absorbed all the cholent goodness.

Jody Spiegel is Director of the Holocaust Survivor Memoirs Program at the Azrieli Foundation.