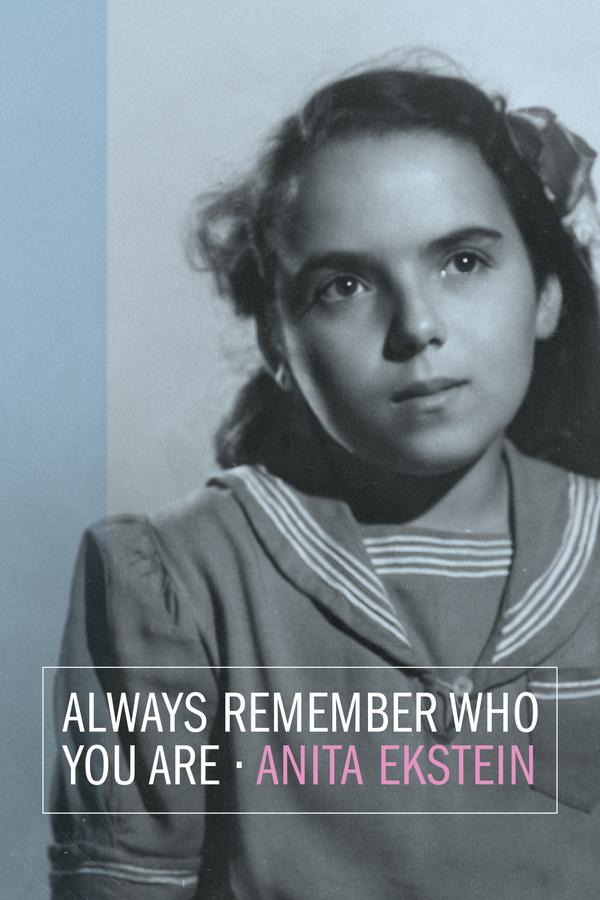

Always Remember Who You Are

“I had to assume a completely new identity and forget who I had been. And the family immediately began to teach me how to be a Catholic.”

When the Nazi Germany invades eastern Poland in 1941, young Anita Ekstein, a cherished only child in a large, close-knit family, is suddenly living in the shadow of fear and violence. At seven years old, she and her parents are forced from their home into a ghetto, and one day, her mother is gone. As Anita’s father desperately tries to save his beloved daughter, he befriends a Catholic man who smuggles Anita out of the ghetto, risking his own life to save hers. Frightened, living among strangers and missing the warmth her parents provided, Anita learns how to be Catholic and spends most of her days inside and in silence. Always at risk of being discovered, Anita has only her newfound faith to accompany her on the lonely path of survival. After the war, orphaned and struggling with her identity, Anita finds her way through her grief and confusion to fulfill her father’s last request to Always Remember Who You Are.

Miraculous Escape

We didn’t know where my mother had been taken. Nobody knew anything in our part of Poland. We had heard rumours of murder by gas. But who could believe this? The Nazis deliberately withheld information from their victims for fear of resistance or reprisal. They were the kings of deception.

After this incident, my father seemed to have lost his will to live but became desperate to protect me, his only child. He knew that if I remained in the ghetto, I would be caught in the next Aktion. He did not know exactly what had happened to those who were taken, but he understood that they were not coming back. We heard that the transports from our region were taken to a camp in the small town of Bełżec.

The rumours that circulated about the mass murders underway there were terrifying. My father no longer kept any secrets from me. Since he was desperately trying to save me, he told me exactly what was going on. I trusted my father and knew that he would do everything in his power to keep me safe.

Once the Germans realized how valuable my father’s accounting skills were, they moved him into the office hut in our hometown permanently. There he came into contact with non-Jews, who were permitted to live outside the ghetto walls. My father quickly befriended a Polish Catholic man, Josef Matusiewicz, who had been brought from his town to serve as the stock-keeper.

[…]

My father did not know where to turn or what to do after the loss of my mother. He was scared of the day when he would come home from work to find that I, too, had disappeared. But asking Josef to help me was a dangerous proposal. In German-occupied Poland, strict laws prohibited people from helping Jews in any way, including providing food rations or hiding Jews in their home. Any person caught or even accused of helping a Jew risked their own life, as well as the lives of their family and, sometimes, communities.

[…]

When he agreed to take me, Josef knew he was violating Nazi law. Josef had not been a family friend, and I did not know him. Many years later, I learned about the night Josef told his wife that he wanted to bring a little Jewish girl into their home. He explained the situation and what he had been asked to do. Josef’s adopted daughter Lusia told me that her mother, Paulina, was dismayed by the request: “Are you crazy? You’re going to bring a little Jewish girl into our house? You’re going to endanger our lives, you cannot do that!” I believe that Josef was an extremely courageous man and responded that God would help. They were a very religious family and fervently believed that God would help them protect me. Josef saw my father’s desperation and could not look away. At tremendous personal risk, the decision was made to take me in.

My father tried to prepare me for another major change. He explained that it was very important that I understood that he could not keep me safe. Every day in the ghetto was dangerous for me. I knew that being Jewish was dangerous. My mother was already gone. I did not want to lose him, too. My father reassured me that I would live with people who would be good to me and care about me. Life would be much better for me there than it was in the ghetto. Before we had come to the ghetto, I was terribly spoiled, an only child. Needless to say, after a year in the ghetto, I was not spoiled any longer. I did not want to go. But my father made it absolutely clear that I had no choice in the matter. I had to go. Otherwise, he told me, I might die. And I had seen death in the ghetto. I am not sure if I understood at the age of eight what it meant to die, but I knew that it was final.

My father assured me that he would be fine, and that we would be together shortly. “It won’t take long. Everything will be fine. I’ll come and see you and I’ll take you home.…” He promised me everything a parent would promise an eight-year-old child. And so, when Josef Matusiewicz came to get me, I went along with him. I was petrified because I didn’t really know this man, whom I had met only a handful of times. I didn’t want to leave my father.

Josef Matusiewicz’s position granted him special access to the otherwise restricted ghetto, and one night he was able to get into the ghetto to collect me. I had to say goodbye to my father. I clung to him and did not want to let go. When we could no longer delay the inevitable, Josef put me in a large bag and carried me out of the ghetto like I was a sack of potatoes. I was cautioned not to make any noise, not to move, not to draw any attention to myself. Years later I learned that there was a police station located right next to where we left the ghetto. I don’t know how Josef managed to take me out. It really was a miracle that we were not caught.

About the Author

Anita Helfgott Ekstein was born on July 18, 1934, in Lwów, Poland (now Ukraine). After the war, Anita and her aunt immigrated to Paris, arriving in Toronto in 1948. A dedicated Holocaust educator, Anita founded a group for child survivors and hidden children in Toronto, participated in the March of the Living eighteen times and has spoken to thousands of students. Anita lives in Toronto.

Anita’s memoir is available for purchase here.